Technical Notes

This project began as a series of typed histology lab notes in 1982, when I was teaching

at Texas A&M. Inexorably, in accordance with the Law Of Academic Paperwork,

over the years the revisions, additions, and expansions of the original increased the size of

the package from a slim 20-odd pages to a bulging 165 page handout,

distributed to the class each year at considerable expense.

The first several versions were written on an IBM Selectric II, a device that represents

the absolute zenith of typewriter technology: no better purely mechanical machine

has ever been made, anywhere, by anyone, period. But it was obsolete even in 1982,

and it's a museum piece now, as dated as coal oil lamps and gentlemen's s pats.

Beginning with the third edition on paper, progressively more up-to-date "word processing" programs were used.

The first several versions were written on an IBM Selectric II, a device that represents

the absolute zenith of typewriter technology: no better purely mechanical machine

has ever been made, anywhere, by anyone, period. But it was obsolete even in 1982,

and it's a museum piece now, as dated as coal oil lamps and gentlemen's s pats.

Beginning with the third edition on paper, progressively more up-to-date "word processing" programs were used.

Update, September 10, 2017: Two days ago I was in a local Goodwill store and came across an apparently brand new Selectric II, absolutely identical to the one I used so many years ago except for color: it was priced at $15, with no takers. These wonderful machines sold for several hundred dollars forty years ago, and I was sorely tempted; but alas, even I have no room in my house for a dinosaur, be it ever so much a bargain. Sic transit gloria mundi.

In the mid 1980's I made the wrenching transition from my reliable and predictable

Selectric to the quirks and idiosyncrasies of Wordstar 3.3, at that time

the cutting edge of "word processing" programs. This was a big leap for

someone who wrote his Ph.D. dissertation—all five drafts of it—on

a manual Smith-Corona portable typewriter dating to the Korean War. No one who has ever learned to use "word processor" software

would ever willingly go back to using a typewriter, but there are times when

I do think fondly of my old blue IBM dinosaur and wonder where it is.

The first "word processing" of the expanded set of notes—still being handed out on paper at that point—was

done around 1984 or 85. This was so early in the game that I wasn't even using a computer running

under DOS. Bill Gates hadn't yet achieved a lock on the personal computer market,

and my first computer was a Kaypro II running some now forgotten CPM software,

and the Wordstar 3.0 version for it. Nor did there exist such a thing as a scanner with optical character recogntion. I had to type the whole damned thing over again.

Despite my misgivings I survived that initial move to "word processing."

That phrase still bothers me, but pushing electrons around seems to merit a different

term than "writing," and after all, it's no more technocratic than "typewriting"

was in, oh, 1895. I draw the line, however, at the use of "keyboard"

as a verb: as in, "I'm going to keyboard that document." That much of

my vocabulary standards remains intact.

By the time I came to Virginia Tech in

1987, the notes I'd accrued (which were still, of course, distributed on paper) needed revision and expansion again. I had moved

up to Wordstar 5.0, which was used to produce the third edition. Along

the way I'd made the change from CPM to DOS and was, like 95% of other computer

users, helping to make Mr. Gates the richest man in America.

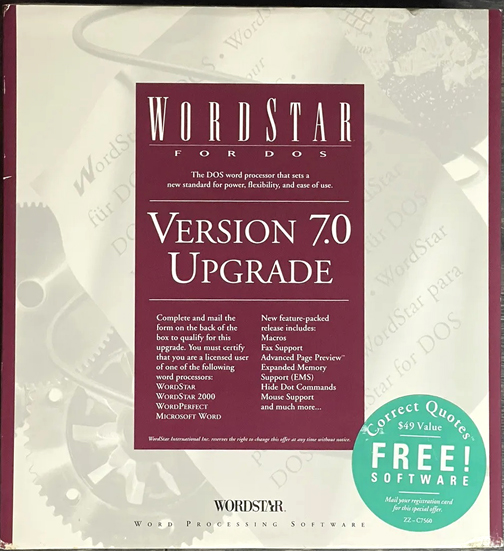

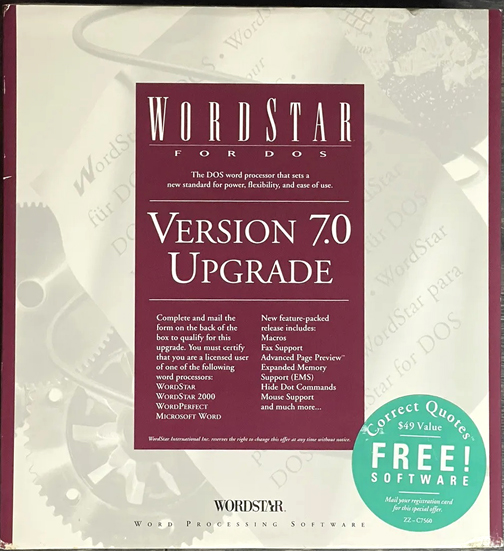

The fourth edition of the lab manual was written in Wordstar 7.0. Between

the time when I started using Wordstar 5.0 and then, I'd actually purchased

version 6.0, but hadn't got around to installing it. I never did. On the very

day that I said to myself, "OK, now I have enough time to install that

new Wordstar," I received a notice in the mail about Version 7.0! So I

ordered that, and version 6.0 still sits moldering in its box. Perhaps someday

in the future a collector of rare early software will be delighted to get it

at my estate auction, still pristine in its shrink wrap.

The fourth edition of the lab manual was written in Wordstar 7.0. Between

the time when I started using Wordstar 5.0 and then, I'd actually purchased

version 6.0, but hadn't got around to installing it. I never did. On the very

day that I said to myself, "OK, now I have enough time to install that

new Wordstar," I received a notice in the mail about Version 7.0! So I

ordered that, and version 6.0 still sits moldering in its box. Perhaps someday

in the future a collector of rare early software will be delighted to get it

at my estate auction, still pristine in its shrink wrap.

The 5th edition of the manual (still on paper) was the transitional one. By the time I began to

write it in early 1995, the world was shifting to Microsoft Word. Word

has the distinct advantage of producing documents that can be read by both PCs

and Mac machines, a matter of considerable importance. If there was ever a version of Wordstar for Macs, I never heard about it.

I was comforted in my affliction to know that between 1987 and 1995 I had

managed to entirely avoid the use of Word Perfect in any form. Word Perfect

was the ne plus ultra of "word processors" at one time, and had eclipsed

the earlier and much better Wordstar entirely. I always hated Word Perfect and was happy

to see it die the death it deserved under the onslaught of Microsoft Word. Nevertheless, just as every now and then a straggler from the Imperial Japanese Army emerges from the Phillippine jungles, there are still some institutions which use Word Perfect. A few days ago I received an attachment in my e-mail written with it and was completely unable to read it.

Unfortunately I was still stuck with the 5th Edition in Wordstar 7.0. I had

to convert the text to Word. It didn't help things that by that time

I was one of perhaps four people left in the USA still using any form of Wordstar

at all.

However, the clever programmers

at Mastersoft had come up with Word for Word, a very slick conversion program

that allowed me to take my Wordstar document and change it over—more or less

perfectly—to anything else. Mercifully I wasn't faced with the horrible prospect

of re-typing all 165 pages of dense, single-spaced, turgid prose as a new document.

Word for Word took all 500 kilobytes of that 5th Edition and created a Word document

in less than ten minutes.

In 1994-95, the surging growth of the World Wide Web made it plain that the days

of paper handouts were numbered. In addition to the enormous bulk, the

costs were rising and seriously pinching the College in a time of budget cuts. The College

was spending well over $40,000 per year for class handouts, and of that total

some $800-900 per year went just to Histology. Obviously something had to be done.

The answer was to devise a paperless version of the manual.

In the final analysis I decided I had to "go digital," and that I had to use something that was "cross platform" that would run on real computers (i.e., PC's) and the never-sufficiently-to-be-cursed Macintosh machines. The University was officially a Mac-based institution, though I fought them fiercely all the way and never did have a Mac on my desk. But I needed something that could be accessed on line by anyone. Given the wide variety of programs then in use for this sort of thing, it was fortuitous that—more or less by accident—I stumbled into the idea of re-working the whole thing for the then-new "World Wide Web." That meant I had to teach myself to write Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), about which I knew nothing whatever.

In its purest form, HTML language is essentially straight ASCII text, and it can be written with any "word processing" software if you know the codes and tags it uses. I knew some basic ones in 1995 but eager software developers were turning out new versions of HTML faster than I could learn them. Furthermore, while Wordstar was a wonderful "word processing" program it wasn't especially good for writing plain ASCII text and of course useless for writing HTML code.

Microsoft Word is a clumsy HTML editor but it's better for the purpose than Wordstar, so as hard as it was for me to abandon my painfully-learned DOS 3.1 and Wordstar, and delve into the mysteries of Windows and Word, I had to do it.

At the time the College faculty

was being asked to devise ways to deliver their information to students at lower

cost. Since I wanted to include many more illustrations than the few line drawings in the paper manuals, and to use color

if possible, writing the revisions as HTML documents and creating a self-contained

WWW site on a CD was the logical next step. The problem was conversion of the

MS-Word version to the HTML format. This was easily solved by acquiring a copy

of an add-on program for MS-Word, Internet Assistant. Internet Assistant

could read a file in early versions of Word and convert it to HTML; later versions of Word do this

automatically. I was set for the emergence of the electronic manual, Version 1.0.

Internet Assistant was a first-generation HTML editor, so I used it only to convert the pre-existing text. All the new

text, all of the original captions for the images, and all the notes and additional material,

were prepared using HTML Writer, a very fine freeware program written by

Kris Nosack at Brigham Young University. HTML Writer was a very early attempt

at making a user-friendly HTML editor and has long since become obsolete as the

WWW has grown and new versions of the HTML language have been developed.

Version

2.0 was edited and re-configured using Corel WebDesigner. Subsequent to that, all versions

have been edited with Macromedia's Dreamweaver programs, starting with Dreamweaver 3.0 and currently Dreamweaver CS3. Dreamweaver is pretty much the standard in HTML editors these days: it's very nearly as easy to use as HTML Writer was and far more powerful.

In addition it has the virtue of being able to strip out of a document the hundreds

of lines of WORD-specific code (read: "gibberish") that result when

using Word to write HTML. The documents Dreamweaver produces are plain-vanilla

HTML code, easy to interpret even in native format.

All the static images of microscopic sections in this site were taken specifically for the project and stored

as .JPG files. Most of them were shot on an Olympus Vanox photomicroscope.

Originally they were recorded on Kodak Ektachrome film and digitized using (ugh) an

Apple Macintosh computer, Photoshop 3.0 software, and a Microtek Scanmaker

1850S slide scanner; then edited with L-View and/or L-View Pro 3.0, for version 1.0. In Versions 1.5 and later editing was done with Photoshop

4.0, 5.0 and 7.0. A Polaroid SprintScan 35LE was used for images scanned from slides after Version 2.0.

In most cases, however, post-Version 1.5 updates include

images that never existed on film at all, thanks to the tremendous improvement in digital image quality in the late 1990's and early 2000's.

They were captured digitally on the

Vanox after retrofitting it first with a Mideo Image Processing system and later with an Olympus DP-70 digital camera. The line

drawings and old photographs were digitized with an Epson 1000C, Paperport 3100, or Paperport 9200 flatbed scanners.

The editing and assembling and re-writing of the first electronic version was

done on a Pionex 486-based PC machine; this old workhorse was put out to pasture

long ago, replaced first by a (shudder) Power MacIntosh, which was replaced in

its turn by a Dell OptiFlex GX1, a Dell Optoplex GX240, and finally a Dell Inspiron 5150 laptop. As of this writing (December 2015) I am using a Hewlett-Packard Elitebook running Windows 7 Enterprise.

Througout the process, though the equipment and (I hope) the final product has been upgraded significantly from where it was a decade ago, the goal has never changed: to present the topic as clearly and as well illustrated as I can. Since in that time I haven't been upgraded, only the user can decide whether this goal has been attained.

Close this Window

The first several versions were written on an IBM Selectric II, a device that represents

the absolute zenith of typewriter technology: no better purely mechanical machine

has ever been made, anywhere, by anyone, period. But it was obsolete even in 1982,

and it's a museum piece now, as dated as coal oil lamps and gentlemen's s pats.

Beginning with the third edition on paper, progressively more up-to-date "word processing" programs were used.

The first several versions were written on an IBM Selectric II, a device that represents

the absolute zenith of typewriter technology: no better purely mechanical machine

has ever been made, anywhere, by anyone, period. But it was obsolete even in 1982,

and it's a museum piece now, as dated as coal oil lamps and gentlemen's s pats.

Beginning with the third edition on paper, progressively more up-to-date "word processing" programs were used.  The fourth edition of the lab manual was written in

The fourth edition of the lab manual was written in