VM8054 Veterinary Histology

Example: Pancreas

Author: Dr. Thomas Caceci

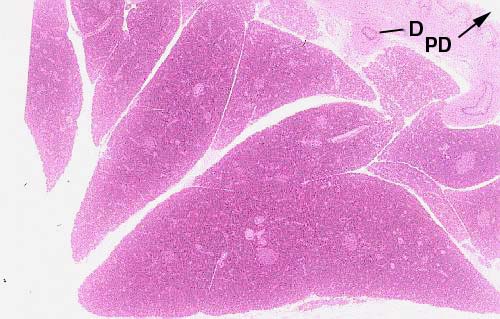

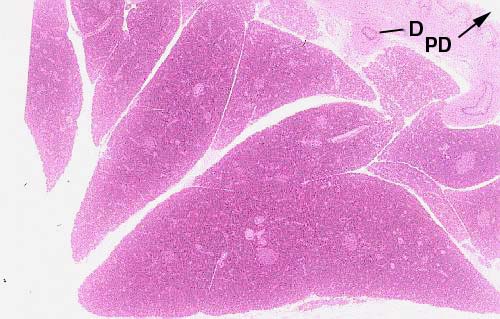

At low magnification, the pancreas can be seen to be extensively

lobulated. As with other lobular organs, there's a

capsule that surrounds the pancreas; CT septae subdivide

it into lobes and lobules. Each of these eosiniophilic regions is a lobe. Blood

vessels and ducts run through the septae.

At low magnification, the pancreas can be seen to be extensively

lobulated. As with other lobular organs, there's a

capsule that surrounds the pancreas; CT septae subdivide

it into lobes and lobules. Each of these eosiniophilic regions is a lobe. Blood

vessels and ducts run through the septae.

The pancreas is a compound acinar gland. An excurrent duct (D)

is visible at the upper right, and this duct is leading into what must be the main pancreatic duct (PD).

At

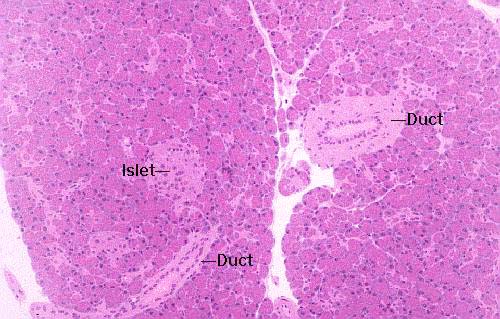

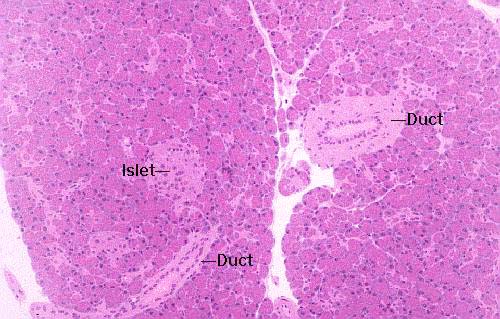

higher magnification the larger ducts in the system are easily visible. They're

lined with a simple columnar epithelium, but this will stratify as the ducts

get large enough.

At

higher magnification the larger ducts in the system are easily visible. They're

lined with a simple columnar epithelium, but this will stratify as the ducts

get large enough.

The output of the exocrine pancreas is channeled through a series of ducts

of increasing caliber, just as in any other exocrine gland, and the nomenclature

is the same. The smallest are the intercalated ducts, each of which serves

only a single secretory acinus. These drain into intralobular ducts,

which in turn drain into interlobular ducts, etc., etc. In most animals

the entire output of digestive enzymes to the intestine is via a single large

pancreatic duct, but an accessory duct is present in some species.

The

concept of the "acinus" is worth showing in a diagram. The acinus

is the basic secretory unit of the pancreas (and many other exocrine glands,

by the way) and it's composed of secretory cells grouped around a lumen into

which their secretions are released. The word "acinus" is from the

Latin for a "berry" or "grape," and what you're seeing in

this sketch is two acini cut along their long axes.

The

concept of the "acinus" is worth showing in a diagram. The acinus

is the basic secretory unit of the pancreas (and many other exocrine glands,

by the way) and it's composed of secretory cells grouped around a lumen into

which their secretions are released. The word "acinus" is from the

Latin for a "berry" or "grape," and what you're seeing in

this sketch is two acini cut along their long axes.

Each of them is built of the secretory cells that produce the

pancreatic enzymes. These cells show basal basophilia, the deep staining

with hematoxylin that's characteristic of any region with a heavy concentration

of RER. The secretory product of these cells is stored in vesicles derived from

the Golgi apparatus and held in the apical cytoplasm until a signal is received

to release them. At that time they're brought to the surface of the cell, the

granules' membranes fuse with the plasma membrane, and the contents are released

intot eh ductwork by exocytosis. The small duct you see in this sketch will

almost immediately join a larger one.

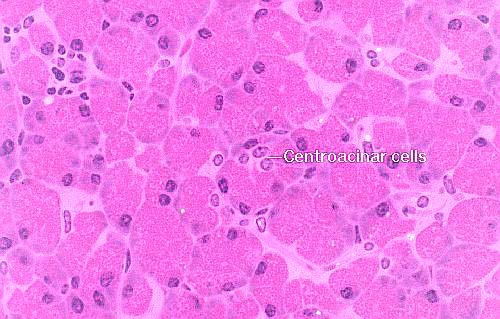

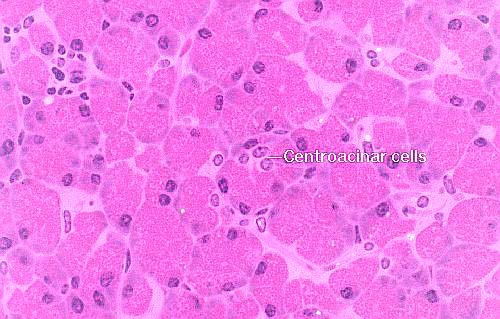

Note also the so-called "centroacinar cells." These

are nothing more than the very first cells in the duct system. They have no

secretory function. They're the actual beginning of the drainage from a given

acinus.

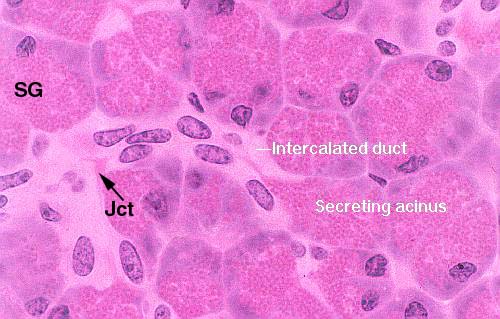

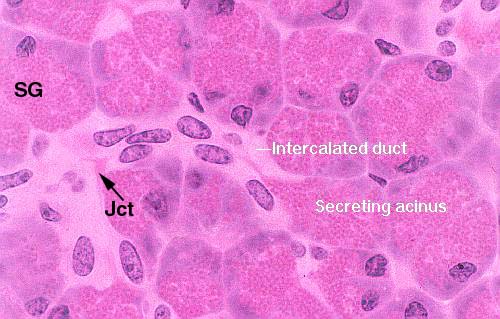

This

is the most "upstream" end of the system. Here you see a secretory

acinus and its individual intercalated duct, cut longitudinally.

The flow is from right to left in this image. Secretory granules (SG)

are held in the cytoplasm of the acinar cells until the signal to release comes.

The release is by exocytosis and the product begins to flow down the ductwork.

This intercalated duct joins with another at a junction point (Jct) to

form a slightly larger intralobular duct, draining two or more acini.

This

is the most "upstream" end of the system. Here you see a secretory

acinus and its individual intercalated duct, cut longitudinally.

The flow is from right to left in this image. Secretory granules (SG)

are held in the cytoplasm of the acinar cells until the signal to release comes.

The release is by exocytosis and the product begins to flow down the ductwork.

This intercalated duct joins with another at a junction point (Jct) to

form a slightly larger intralobular duct, draining two or more acini.

The secretory product is released into the ducts in an inactive form and become

activated when it reaches the intestine. The reason for this is obvious: the

enzymes in it would destroy the pancreas itself before ever reaching the intestine

if released in the active form.

Frequently

an acinus is cut in such a way as to reveal only the first few cells in the

duct system. These are tucked right up a short way inside the acinus,

rather like the stem on a grape. Since they aren't secretory, they'll be stained

differently than the secretory cells. The classical histology term for these

is the centroacinar cells. They're just the first cells of the intercalated

duct.

Frequently

an acinus is cut in such a way as to reveal only the first few cells in the

duct system. These are tucked right up a short way inside the acinus,

rather like the stem on a grape. Since they aren't secretory, they'll be stained

differently than the secretory cells. The classical histology term for these

is the centroacinar cells. They're just the first cells of the intercalated

duct.

Drawing by Dr. Samir El-Shafey

Monkey pancreas; H&E stain, 1.5 µm plastic sections, 20x, 40x,

1000x, and 1000x

Lab Exercise List

At low magnification, the pancreas can be seen to be extensively

lobulated. As with other lobular organs, there's a

capsule that surrounds the pancreas; CT septae subdivide

it into lobes and lobules. Each of these eosiniophilic regions is a lobe. Blood

vessels and ducts run through the septae.

At low magnification, the pancreas can be seen to be extensively

lobulated. As with other lobular organs, there's a

capsule that surrounds the pancreas; CT septae subdivide

it into lobes and lobules. Each of these eosiniophilic regions is a lobe. Blood

vessels and ducts run through the septae.

At

higher magnification the larger ducts in the system are easily visible. They're

lined with a simple columnar epithelium, but this will stratify as the ducts

get large enough.

At

higher magnification the larger ducts in the system are easily visible. They're

lined with a simple columnar epithelium, but this will stratify as the ducts

get large enough.  The

concept of the "acinus" is worth showing in a diagram. The acinus

is the basic secretory unit of the pancreas (and many other exocrine glands,

by the way) and it's composed of secretory cells grouped around a lumen into

which their secretions are released. The word "acinus" is from the

Latin for a "berry" or "grape," and what you're seeing in

this sketch is two acini cut along their long axes.

The

concept of the "acinus" is worth showing in a diagram. The acinus

is the basic secretory unit of the pancreas (and many other exocrine glands,

by the way) and it's composed of secretory cells grouped around a lumen into

which their secretions are released. The word "acinus" is from the

Latin for a "berry" or "grape," and what you're seeing in

this sketch is two acini cut along their long axes. This

is the most "upstream" end of the system. Here you see a secretory

acinus and its individual intercalated duct, cut longitudinally.

The flow is from right to left in this image. Secretory granules (SG)

are held in the cytoplasm of the acinar cells until the signal to release comes.

The release is by exocytosis and the product begins to flow down the ductwork.

This intercalated duct joins with another at a junction point (Jct) to

form a slightly larger intralobular duct, draining two or more acini.

This

is the most "upstream" end of the system. Here you see a secretory

acinus and its individual intercalated duct, cut longitudinally.

The flow is from right to left in this image. Secretory granules (SG)

are held in the cytoplasm of the acinar cells until the signal to release comes.

The release is by exocytosis and the product begins to flow down the ductwork.

This intercalated duct joins with another at a junction point (Jct) to

form a slightly larger intralobular duct, draining two or more acini.  Frequently

an acinus is cut in such a way as to reveal only the first few cells in the

duct system. These are tucked right up a short way inside the acinus,

rather like the stem on a grape. Since they aren't secretory, they'll be stained

differently than the secretory cells. The classical histology term for these

is the centroacinar cells. They're just the first cells of the intercalated

duct.

Frequently

an acinus is cut in such a way as to reveal only the first few cells in the

duct system. These are tucked right up a short way inside the acinus,

rather like the stem on a grape. Since they aren't secretory, they'll be stained

differently than the secretory cells. The classical histology term for these

is the centroacinar cells. They're just the first cells of the intercalated

duct.