|

|

Feline Heartworm Disease

Clarke E. Atkins, D.V.M.,

Diplomate, A.C.V.I.M (Internal Medicine and

Cardiology)

William G. Ryan, M.B.A., B.V.Sc.

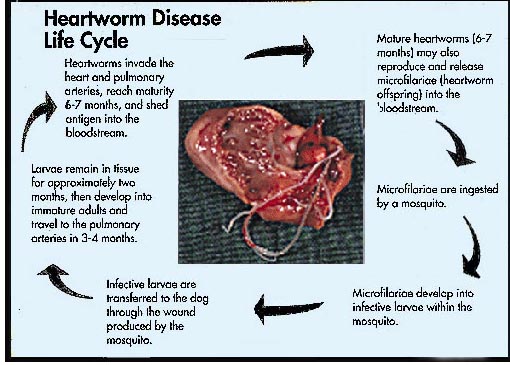

Infection of a cat with Dirofilaria immitis

was first recognized in the United States in 1922. There have been numerous

subsequent reports, with a recent review of 156 previously reported cases.

Despite this, feline heartworm disease (FHWD) has generally been considered a

novelty, with many veterinarians still believing that the cat is not at risk.

This is an unfortunate misconception, as not only is the cat susceptible, but

also its clinical signs are more severe than those of the dog, even when the

worm burden is quite small. In recent years, increasing awareness has brought

the development of better diagnostic tests, efforts at establishing a

satisfactory adulticidal therapy, increasing public awareness, and, recently,

the registration of a feline heartworm preventive.

|

|

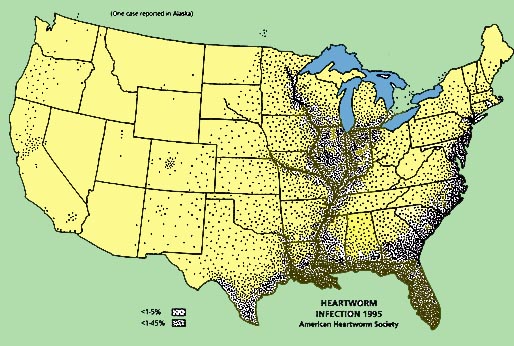

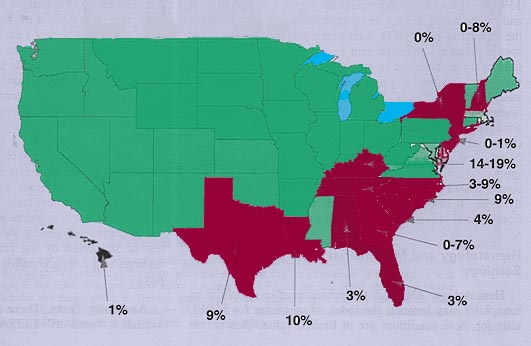

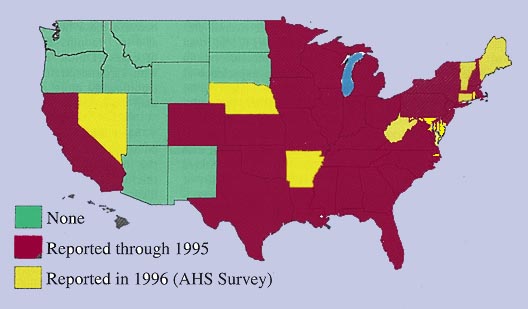

A review of studies reporting

feline heartworm infection (FHWI) and a survey of veterinary practitioners

revealed that the diagnosis has been made in 38 of the 50 United States. Not

surprisingly, the greatest numbers of cases have been reported from the

southeastern United States, the Eastern Seaboard, and the Gulf Coast and within

the Mississippi River valley. Prevalence studies have focused mainly on cats

from shelters. While this population choice has allowed the use of the

relatively sensitive and very specific postmortem diagnosis, these studies are

not necessarily applicable to pet cats, even in the same geographic region.

These 12 studies, from 10 southeastern states, have revealed a prevalence of

FHWI ranging from 0 to 16%. There are limited data in pet cats, but a joint

study, performed on such cats presented to the teaching hospitals of North

Carolina State University (NCSU) and Texas A&M University for evaluation of

cardiorespiratory signs, demonstrated an infection prevalence of 9% and an

exposure rate of 26%, the latter figure based on antibody titers. A number of

serologic surveys, largely in asymptomatic cats, have demonstrated exposure

rates (antibody seropositivity) of 5 to 36%, even in areas not considered

heavily heartworm endemic and as high as 43% in asymptomatic cats.

|

|

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of FHW1 or FHWD poses a unique and problematic

set of issues. First, the clinical signs in cats are often

quite different

from those in dogs. Then, the diagnostic effort is often inadequate because the

suspected incidence in cats is

low. Furthermore, the diagnosis is often

elusive because eosinophilia is transient or absent; electrocardiographic

findings are

minimal; and most cats are amicrofilaremic. Radiography, while

helpful, is neither adequately sensitive nor specific and

requires expertise

in interpretation. Echocardiography shows promise in terms of specificity but is

costly and only moderately sensitive, and requires special equipment and

expertise. Currently, the most useful tests include ELISA serologic tests. These

too are imperfect. The antigen test is very specific but is inadequately

sensitive, missing over 50% of natural infections. On the other hand, a recently

developed feline antibody test is very sensitive, but its specificity is low,

meaning that a positive test indicates -exposure, but not necessarily adult

infection.

While no breeds of cat have been shown to be a increased

risk for FHWI, most authors do suspect a male predisposition.

This suspicion

is based on the overall preponderance of male cats diagnosed with FHWI

and the greater experimental infection rate in males than in females. The

experience at NCSU suggests, however, that while more males (61%) than females

are indeed diagnosed with FHWI, the male-to-female ratio is not significantly

different from that of the general population of cats seen at a teaching

hospital or the population of cats presented with cardiorespiratory signs;. The

typical cat with FHWI is 4 to

6 years of age (range <1 to 19 years). The

history of outdoor exposure would logically predict a heightened risk of FHWI;

the experience at NCSU indicates that this is true. Nevertheless, one third

of heartworm-infected cats are reported by their owners to be housed totally

indoors. This may mean that owners misinterpret the question as to whether their

pet goes outdoors or that indoor cats can be infected, or both. Although a

seasonal incidence (August to December) has been suggested for FHWD, other

studies do not support this contention.

Heartworm-infected cats may be

asymptomatic, and clinical manifestations, when present, may take either an

acute (often cataclysmic) or a chronic (often waxing and waning) course. Acute

or peracute presentation is usually due to dead worm embolization or migration

of worms to the central nervous system, and signs variably include salivation,

tachycardia, shock, dyspnea, cough or hemoptysis, vomiting and diarrhea,

syncope, dementia, ataxia, circling, head tilt, blindness, seizures, and death.

Sudden death, with little or no premonitory signs, has been observed in

approximately 23% of cases. Cats that die suddenly may appear clinically normal up to 1 hour before

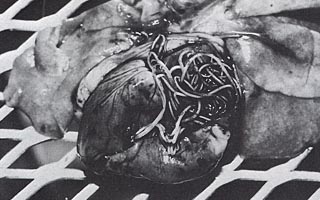

death. Postmortem examination has revealed as few as two worms in cats

that have died suddenly.

Postmortem examination typically reveals pulmonary infarction with congestion

and edema. Vena caval syndrome has also been recognized in

cats.

|

|

Findings in chronic FHWD may include cough, dyspnea, anorexia, weight loss, lethargy, exercise intolerance, vomiting, and signs of right-heart failure. Cough is a relatively consistent finding (>50% of cases, compared with 15% in cats with cardiorespiratory signs, but not FHWI and, when noted in cats in endemic areas, should increase the suspicion of FHWD. Likewise, dyspnea, though less specific than cough, is present in 40 to 60% of cases. The pulmonary response to in situ heartworms in cats includes type 11 cell hyperplasia and activation of pulmonary intravascular macrophages. This response, not recognized in dogs, may explain the astlima-like syndrome recognized in some cats, even after they have been cleared of D. immitis.

Physical examination is often unrewarding, although a murmur, gallop, and/or diminished or adventitial lung sounds may be noted. In addition, cats may be thin and/or dyspneic. If heart failure is present, jugular venous distention, pleural effusion, and rarely ascites are detected

Hematology. Although the presence of

eosinophilia or basophilia may increase the index of suspicion for FHWL tests

for these conditions are of limited value. This is true because these

hematologic changes are transient (present at 4 to 7 months after infection) and

present in only 33% of cases. In a prospective study of cats with

cardiorespiratory signs, those with FHWD were not significantly more apt to have

eosinophilia or basophilia than those not shown to be infected.

Microfilarial Tests. A definitive diagnosis of FHWl can be made by the detection of circulating microfilariae, using the modified Knott test, millipore filter, direct smear, or microhematocrit techniques. A recent literature review indicated that 36% of 45 cats with FHWD were microfilaremic, while other reports have indicated no more than 20% of infected cats are microfilaremic. This discrepancy probably reflects the fact that at the time of early reports diagnostic methods were limited to microfilarial tests and postmortem examination. While increasing the volume of blood samples, multiple testing, and drawing evening samples may increase the diagnostic efficiency of the microfilariadependent tests, the low percentage of cats that become microfilaremic, the transient nature of microfilaremia, and the low microfilarial numbers seriously limit their utility.

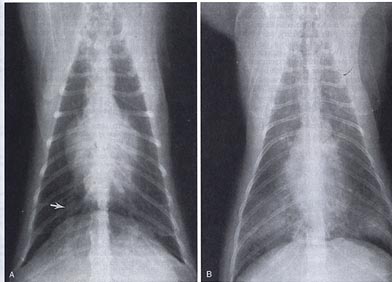

Radiography. Radiographic findings of FHWD include enlarged caudal pulmonary arteries, often with ill-defined margins; pulmonary parenchymal changes, including focal or diffuse infiltrates (interstitial, bronchointerstitial, or even alveolar); perivascular density; and, occasionally, atelectasis or pleural effusion. Pulmonary hyperinflation and right-heart enlargement may also be evident. Thoracic radiography has been suggested as an excellent screening test for FHWD. However, while often helpful, thoracic radiography is neither sensitive nor specific in making the diagnosis of FHWD. The single most sensitive radiographic criterion (left caudal pulmonary artery diameter greater than 1.6 times that of the ninth rib at the ninth intercostal space) can be identified in only 53% of cases and may also be noted in cats with heart failure, but not FHWI. Likewise, pulmonary parenchymal changes are only detectable radiographically in approximately 50% of natural cases. Even though most cats with clinical signs have some radiographic abnormality, the findings are not specific for FHWD, are variable, and are often transient. Lastly, radiographic abnormalities have been detected in experimentally exposed cats that ultimately resisted heartworm maturation and were negative on postmortem examination (i.e., false-positive). On the other hand, pulmonary angiography can be used to make a definitive diagnosis by the demonstration of radiolucent intravascular "foreign bodies," as well as enlarged, tortuous, and blunted pulmonary arteries.

A,Thoracic radiograph from a

cat with mild radiographic signs of heartworm disease. Note the right caudal

pulmonary artery (arrow). The arrow is located in the ninth intercostal space,

the site for comparison of the ninth rib with the pulmonary artery (right or

left side). If the pulmonary artery is greater than 1.6 times the size of the

rib, it is suggestive of heartworm disease (Schafer and Berry, 1995). B,

Thoracic radiograph obtained from a more severely affected cat. Note the

alveolar infiltrate in the caudal lung lobes. (From Schafer M, Berry CR: Cardiac

and pulmonary artery mensuration in feline heartworm disease. Vet Radiol

Ultrasound 36:499, 1995.)

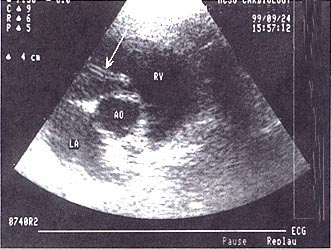

Echocardiography. Echocardiography

is more sensitive in cats than in dogs for the detection of heartworm infection.

Typically, a "double-lined echodensity" (Fig. 4) is evident in the main

pulmonary artery, one of its branches, or the right ventricle, or occasionally

at the right atrioventricular junction. FHWI was detected echocardiographically

in 7 of 9 natural cases and 12 of 16 experimental infections. A retrospective

review of a larger case series revealed a lower sensitivity when worms were not

specifically sought and, particularly, when studies were performed by

noncardiologists. This observation underscores the need for a high index of

suspicion and expertise if this technique is to be of value in the diagnosis of

FHWI.

|

|

PREVENTION

Even though there is no reason to expect adverse reactions to prophylaxis in cats with existing FHWI, it could be useful to know the heartworm status of cats prior to the administration of a preventive. The current ELISA antigen tests have not yet been shown to be adequately sensitive for this purpose, unless the client is properly educated as to the limitations of the test. The ELISA antibody test (alone or with an antigen test) is currently more appropriate because of its higher sensitivity and ability to identify cats at risk (infected or exposed). While screening for FHWI before the administration of a preventive is not absolutely necessary, client education as to the possibility of preexisting infection is imperative.

Based on disease severity, the lack of an effective and safe

adulticidal therapy, and the difficulty in making a definitive diagnosis, the

authors believe that cat owners in endemic areas should be offered the choice of

their pet receiving a heartworm preventive. Clearly, cats already infected with

heartworms and their house mates should be placed on a

preventive.

References

Atkins CE, DeFrancesco TD, Miller M, et al: Prevalence of

heartworm infection in cats with signs of cardiorespiratory abnormalities.

J

Vet Med Assoc 212:517, 1997.

A prospective survey of the prevalence of heartworm infection in North Carolina and Texas cats with cardiorespiratory abnormalities. Prevalence, risk factors, and comparisons of diagnostic tests are provided.

Atkins CE: Veterinary CE Advisor: Heartworm disease: An

update. Vet Med (Suppl) 93:12:2, 1998a.

A comprehensive and very current

review of the diagnosis and preven tion of heartworm infection in dogs and

cats.

Atkins CE, DeFrancesco TD, Coats J, et al: Feline Heartworm

Disease The North Carolina Experience. In: Soll MD, Knight DH, eds:

Proceedings of the American Heartworm Symposium '98. Batavia, IL American

Heartworm Society, 1998b.

Retrospective analysis of the risk factors, clinical

presentation, diag nostic test results, and survival of 50 cats with heartworm

infection.

Clark JN, Pulliam JD, Alva R, et al: Safety of orally

administered ivermectin in cats. In: Soll MD, ed: Proceedings of the Heartworm

Symposium '92. Batavia, IL: American Heartworm Society, 1992, p

103.

Documents the safety of high-dose ivermectin in adult cats.

DeFrancesco TD, Atkins CE, Miller MW, et al: Diagnostic

utility of echocardiography in feline heartworm disease. In: Soll MD, Knight DH,

eds: Proceedings of the American Heartworm Symposium '98.. Batavia, IL:

American Heartworm Society, 1998.

A review of a number of reports of the

efficacy of echocardiography in the diagnosis offeline heartworm

infection.