Pongo's a 7-year old Newfoundland Retriever. His owner is concerned because one day when he was playing with him he noticed a "lump" on Pongo's belly. He brings the dog to you for examination.

The "lump" is soft and moveable, about 3 cm across, painless, and located under the skin. You take an aspirate and find the smear to contain what appear to be mature white adipose cells. Your diagnosis is that Pongo has a cutaneous lipoma. You tell the owner not to be too concerned, and that unless the lesion gets large enough to bother the dog in some way, to leave it alone.

Points to ponder:

1. What cell type(s) is (are) involved in the development of this growth?

2. Why is this abnormal behavior for these cells?

3. In general terms, what seems to have happened to precipitate the behavior?

DISCUSSION

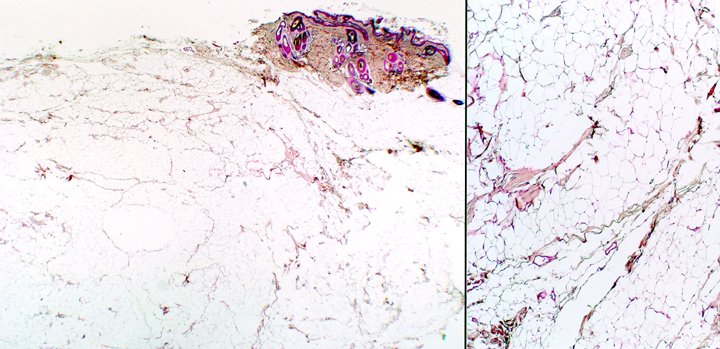

Cutaneous lipomas are very common. They're benign tumors of connective tissue named after their cell of origin, the white adipocyte (fat cell). Lipomas show up in older dogs, and a Newfie is getting to Senior Citizen status at age 7, so it's not surprising that Pongo's got at least one; and he'll likely get more as time goes on. Had Pongo's been excised it would have looked like the one at left: well-demarcated and discrete, basically a lump of soft fat. Microscopically the tissue is indistinguishable from any other white fat depository, as you can see below: it has the "chicken wire" look.

Cutaneous lipomas are very common. They're benign tumors of connective tissue named after their cell of origin, the white adipocyte (fat cell). Lipomas show up in older dogs, and a Newfie is getting to Senior Citizen status at age 7, so it's not surprising that Pongo's got at least one; and he'll likely get more as time goes on. Had Pongo's been excised it would have looked like the one at left: well-demarcated and discrete, basically a lump of soft fat. Microscopically the tissue is indistinguishable from any other white fat depository, as you can see below: it has the "chicken wire" look.

What triggers a lipoma to to occur isn't known, but in general, something causes the cells to begin dividing when they normally wouldn't. Now, white fat cells are very highly differentiated, having achieved their final maturity, and definitive morphological appearance. These long-lived cells (whose existence is measured in decades) don't divide, they just get larger or smaller as their lipid content increases or decreases.

When a cell population that's not supposed to divide starts doing so, something is wrong. Since all cells have the same "blueprint" in their DNA, the information on how to divide is still present in the genome. Whatever triggers a lipoma causes the cell to begin reading and translating genes for enzymes in the division cycles. Differentiated or not, the cells begin to replicate. An aspirate will show what are essentially mature fat cells, because about all they've done is add this somewhat unusual activity to their repertoire: they're still fat cells in appearance and in other respects.

Lipomas usually grow fairly slowly, and if they're arising in the fat layer under the skin, don't generally cause major problems. Rarely, a lipoma will form in the fat of the mesenteries. If it enlarges enough it may cause displacement of organs and/or compression of blood vessels. So-called "infiltrative lipomas" can form in the fat associated with skeletal muscle. These can be excised but may recur because of local invasion between muscle planes. They aren't metastatic, however.

Since cutaneous lipomas are common, benign, and usually cause no discomfort, the usual advice given is to leave them alone. But...there's another tumor of fat origin, the liposarcoma. These are invasive and metastatic. If the aspirate shows only fat cells, it's probably a lipoma; but unfortunately it's possible to misread a liposarcoma, if the aspiration procedure strikes only fat. An excised lump should be sent to a pathology lab to be read, so as to rule out the more serious situation.

References:

Bergman PJ, Withrow SJ, Straw RC, Powers BE. 1994. Infiltrative lipoma in dogs: 16 cases (1981-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 205(2):322-4.

Miles J, Clarke D. 2001. Intrathoracic lipoma in a Labrador retriever. J Small Anim Pract. 2001 Jan;42(1):26-8.

Mayhew PD, Brockman DJ. 2002. Body cavity lipomas in six dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2002 Apr;43(4):177-81.