CASE DISCUSSION

A "leukemia" strictly defined, is a condition of increased numbers of white blood cells, i.e., a malignant tumor of the cell lines leading to leukocytes, and typically characterized by large numbers of the tumor cells in circulation. It's really a sort of "umbrella" term that covers a host of more-specifically defined conditions. Lymphoma (lymphosarcoma) is the most common malignancy diagnosed in cats; lymphoma in young cats occurs most frequently following infection with Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV), shown at right in an electron

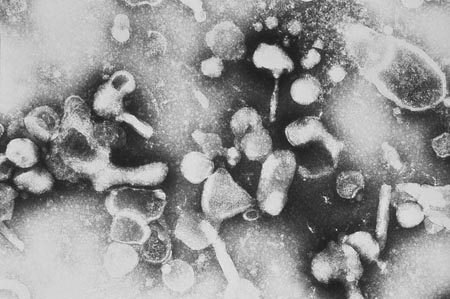

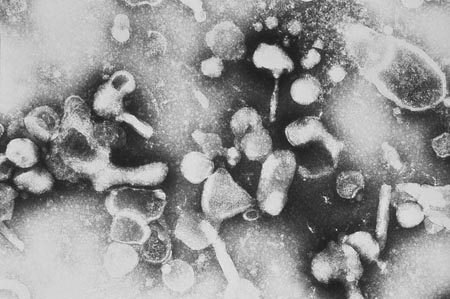

A "leukemia" strictly defined, is a condition of increased numbers of white blood cells, i.e., a malignant tumor of the cell lines leading to leukocytes, and typically characterized by large numbers of the tumor cells in circulation. It's really a sort of "umbrella" term that covers a host of more-specifically defined conditions. Lymphoma (lymphosarcoma) is the most common malignancy diagnosed in cats; lymphoma in young cats occurs most frequently following infection with Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV), shown at right in an electron  microscope preparation. FeLV is a retrovirus, i.e., one in which the viral information is carried in RNA, not DNA.

microscope preparation. FeLV is a retrovirus, i.e., one in which the viral information is carried in RNA, not DNA.

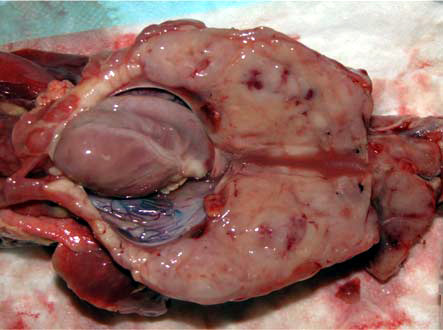

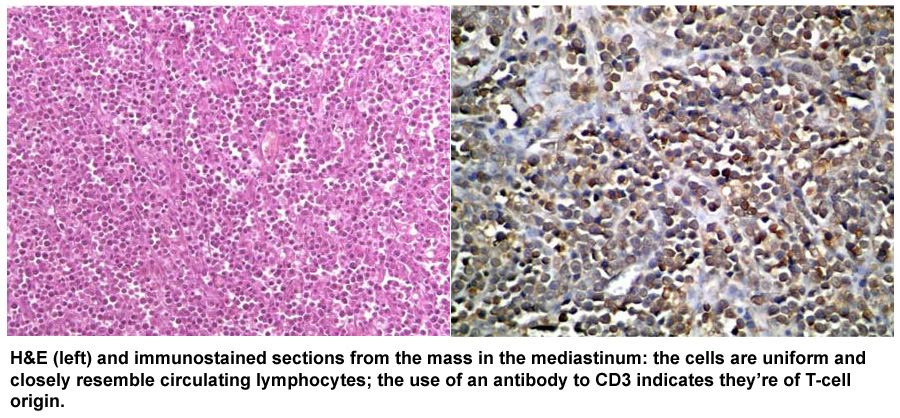

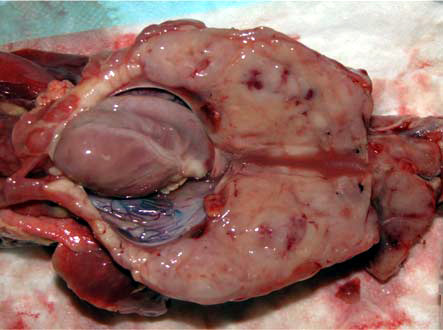

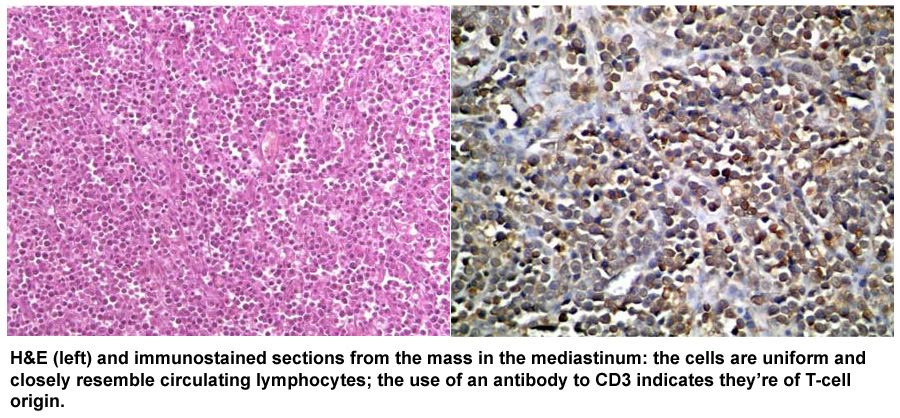

FeLV-positive cats that develop lymphoma typically have involvement of lymph nodes in the mediastinum; and they're 62 times more likely to develop lymphoma than FeLV-negative cats are. At necropsy, the anterior mediastinal area was occupied by a homogenous soft tan mass, with the heart incarcerated inside (left). This mass and the mediastinal tissue were examined microscopically and showed uniform (monomorphic) lymphoid cells, which stained positive using immunolabeling for T-lymphocyte markers: this tumor was derived from T-cells, not B-cells (right).

Cats that develop lymphoma are much more likely to develop more severe symptoms than dogs. Whereas dogs often appear healthy initially except for swollen lymph nodes, cats will often be physically ill. The symptoms correspond closely to the location of the lymphoma. Hence Rocky's symptom labored breathing: the mass of tumor in the mediastium was pressing on his lungs and the effusion of fluid interfered with breathing and heart action.

Not all cats exposed to the virus develop a continuing burden of it: if they have a good immune response they may extinguish it and become immune to further infection. They may also become tolerant of its presence and become asymptomatic carriers. The likelihood is that Rocky was exposed as a very young kitten—possibly from his mother—and hence was FeLV-positive from the day he showed up, so there wasn't much the owner could have done; but he should be advised that any new cats coming into the household be tested for FeLV, and vaccinated against it if they show up negative. The use of the vaccine has greatly reduced the incidence of FeLV-related lymphoma in the past decade or so, but not completely eliminated it.

Not all cats exposed to the virus develop a continuing burden of it: if they have a good immune response they may extinguish it and become immune to further infection. They may also become tolerant of its presence and become asymptomatic carriers. The likelihood is that Rocky was exposed as a very young kitten—possibly from his mother—and hence was FeLV-positive from the day he showed up, so there wasn't much the owner could have done; but he should be advised that any new cats coming into the household be tested for FeLV, and vaccinated against it if they show up negative. The use of the vaccine has greatly reduced the incidence of FeLV-related lymphoma in the past decade or so, but not completely eliminated it.

Even though they may not develop a tumor, FeLV-positive cats are at risk for other diseases, especially infectious ones, because their immune systems are compromised. If the virus has gained a footing in the marrow, the cat is infectious and must be sequestered from other cats to prevent passing it on to them in saliva or nasal secretions, as can easily happen if cats share a food bowl or litter pan, for example.

References:

Antony, S.M., and K.O. Gregory. "Lymphoma." 2001. In: Feline Oncology. Veterinary Learning Systems, Yardley, PA. pp. 191-219.

Crighton, G.W. 1968. Clinical aspects of lymphosarcoma in the cat. Veterinary Record 83: 122-126.

Gruffydd-Jones, T.J., C.J. Haskell, and C. Gibbs. 1979. Clinical and radiological features of anterior mediastinal lymphosarcoma in the cat: a review of 30 cases. Veterinary Record 104:304-307.

A "leukemia" strictly defined, is a condition of increased numbers of white blood cells, i.e., a malignant tumor of the cell lines leading to leukocytes, and typically characterized by large numbers of the tumor cells in circulation. It's really a sort of "umbrella" term that covers a host of more-specifically defined conditions. Lymphoma (lymphosarcoma) is the most common malignancy diagnosed in cats; lymphoma in young cats occurs most frequently following infection with Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV), shown at right in an electron

A "leukemia" strictly defined, is a condition of increased numbers of white blood cells, i.e., a malignant tumor of the cell lines leading to leukocytes, and typically characterized by large numbers of the tumor cells in circulation. It's really a sort of "umbrella" term that covers a host of more-specifically defined conditions. Lymphoma (lymphosarcoma) is the most common malignancy diagnosed in cats; lymphoma in young cats occurs most frequently following infection with Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV), shown at right in an electron  microscope preparation. FeLV is a retrovirus, i.e., one in which the viral information is carried in RNA, not DNA.

microscope preparation. FeLV is a retrovirus, i.e., one in which the viral information is carried in RNA, not DNA.

Not all cats exposed to the virus develop a continuing burden of it: if they have a good immune response they may extinguish it and become immune to further infection. They may also become tolerant of its presence and become asymptomatic carriers. The likelihood is that Rocky was exposed as a very young kitten—possibly from his mother—and hence was FeLV-positive from the day he showed up, so there wasn't much the owner could have done; but he should be advised that any new cats coming into the household be tested for FeLV, and vaccinated against it if they show up negative. The use of the vaccine has greatly reduced the incidence of FeLV-related lymphoma in the past decade or so, but not completely eliminated it.

Not all cats exposed to the virus develop a continuing burden of it: if they have a good immune response they may extinguish it and become immune to further infection. They may also become tolerant of its presence and become asymptomatic carriers. The likelihood is that Rocky was exposed as a very young kitten—possibly from his mother—and hence was FeLV-positive from the day he showed up, so there wasn't much the owner could have done; but he should be advised that any new cats coming into the household be tested for FeLV, and vaccinated against it if they show up negative. The use of the vaccine has greatly reduced the incidence of FeLV-related lymphoma in the past decade or so, but not completely eliminated it.